From Ryukyu to Zheng He Island: The Covert Struggle for the First Island Chain Under the Guise of Nationalism

When Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi made the statement, “A Taiwan contingency is a Japanese contingency,” the Chinese public sphere was instantly flooded with discussions about “Ryukyu (Okinawa) independence” and “China’s sovereignty claims over Ryukyu.” This historical hype targeting Ryukyu is by no means a spontaneous academic revival; its essence is the systemic populist emotional manipulation of the historical ‘victimhood complex’ by political forces amidst escalating geopolitical conflict. This rhetoric constructs sovereignty and territory as a sacred, indivisible whole, using political emotion to mask historical multiplicity.

We must return to the root of this “victim” narrative and deconstruct its historical reality as a successful great power to understand how it has been extended to Ryukyu, and to extreme, unfounded claims such as “Zheng He Island.”

I. Universal Shock and Specific Memory: The De-mythologization of the “Century of Humiliation”

The “Century of Humiliation,” as a grand historical and political narrative, initially reflected the genuine psychological shock felt by Chinese intellectuals facing a completely new geopolitical landscape: the descent from the traditional center and apex of the *Tianxia* (All-Under-Heaven) order to merely one member of the global geopolitical system. This immense psychological gap and the disintegration of the “center” identity (e.g., the center-focused view on Chinese world maps) were objectively real.

However, ceding territory and paying indemnities were by no means unique to China—they were universal phenomena during that era of global geopolitical transformation, and furthermore, they were an inevitable result that the losing party had to face. Spain, during the same period, lost almost all its overseas territories after the Spanish-American War; France ceded land and paid indemnities after the Franco-Prussian War; and Russia suffered significant losses in the Crimean War. The “humiliation” narrative put forth by figures like Liang Qichao was initially possibly an honest reaction to the psychological shock brought about by the collapse of the *Tianxia* system;

In understanding these highly politicized historical narratives, we must reflect on a fundamental question: Sovereignty itself is not an emotional entity. Sovereignty is an institutional classification—a legal status concerning effective control, jurisdiction, and international recognition; it cannot be “humiliated” (受辱) or “vindicated” (雪恥). Those who truly feel historical tragedy and suffering are the individuals and communities living through history, not the abstract concept of sovereignty. Personifying sovereignty, describing legal and institutional shifts as “national humiliation” or “ethnic shame,” is essentially a political narrative technique used to solidify group identity, manufacture moral mobilization, and incite external hostility. This narrative transforms real historical experience into an emotional framework, which is then used to legitimize modern political goals. However, historical tragedy cannot automatically translate into contemporary territorial claims, nor can collective memory constitute the legal basis for sovereign change. Conflating emotion with sovereignty, and memory with jurisdiction, only makes discussion heated yet hollow, allowing geopolitics to slide more easily toward emotionalism and extremism.

but as modern political forces ideologically prolonged and amplified it, its function shifted to populist emotional manipulation of the populace, aimed at diverting internal conflicts and deliberately obscuring China’s reality as a successful great power.

II. The Forgotten Great Power: Qing Empire’s Territorial Consolidation and Multi-layered Rule

Nationalists inherited the “humiliation” rhetoric to oppose the Qing monarchy, simplifying the complex Qing state matrix into a “centralized unitary state.”

The Qing political structure was far more complex than this simplified narrative; it was essentially a Multi-Sovereign Federation under a Composite Monarchy. Its ruling structure was maintained through the Board of Colonial Affairs (理藩院) governing Mongolia, the Resident Commissioners (駐藏大臣) supervising Tibet (Gaxag), the General of Ili managing Xinjiang, and the Emperor’s multiple titles.

Particularly in the Xinjiang region, the Qing Dynasty not only successfully defended its territory during the mid-19th century Sino-Russian conflicts but also established direct provincial administration in areas previously only indirectly controlled, integrating them into the central government’s direct management system. This clearly demonstrates that China was not merely a victim in modern history but a great power capable of expanding and consolidating territory amidst competition. This capacity is rare globally; only a few states, such as China, Russia, and the United States, ultimately consolidated their territorial expansion gains, while older colonial powers like the UK, France, Spain, and the Netherlands have faded into history.

III. The Compromise of Power: “Situational Equivalence” and Treaty Politics under International Law

The so-called “Unequal Treaties” were likewise symbolized by subsequent political narratives. In reality, these treaties were products of international political compromise. The consideration (quid pro quo) of treaties is often determined by context—under specific historical moments and conditions of power imbalance, an exchange might be deemed “situationally equivalent” at the time (like exchanging resources for a cup of water in a desert), only to appear grossly unequal after the passage of time. The Treaty of Nanking, which exchanged open ports and indemnity payments for peace, contained rights and responsibilities agreed upon by the Qing court and Britain within the prevailing international order, given that the Qing had lost the war.

Interpreting them purely as “humiliation” is largely an emotional interpretation fabricated later to provide political justification for subsequent unilateral treaty abrogation and bad faith actions. Successor regimes utilize this historical grievance as a tool for political legitimacy and populist mobilization. In fact, treaties involving territorial cession and indemnity payments are not uncommon in international politics, and ongoing conflicts, such as the current Russian-Ukrainian ceasefire negotiations, may include such terms.

IV. The Myth of Sovereignty: Ryukyu’s “Dual Vassalage” and Fabricated Historical Claims

Issues concerning Taiwan, Xinjiang, and Tibet are essentially questions of sovereignty philosophy being instrumentalized. Nationalists imagine Chinese sovereignty as a sacred, indivisible whole, but this obscures the historical reality of late Qing China as a cluster of multi-sovereign units—localities enjoyed varying degrees of autonomy and differentiated legal status at different times (e.g., the high autonomy granted to the Tibetan Gaxag by the Qing court). This selective reading transforms “indivisible sovereignty” into a political myth.

Notably, this rhetoric framework is being extended to current international operations:

- The Hype Around Ryukyu and its Historical Reality: Ryukyu historically maintained a tributary relationship with China, but its status was more complex: the Ryukyu Kingdom was effectively a “dual vassal” that paid tribute concurrently to the Qing Dynasty and the Japanese Shimazu clan of Satsuma. Within the Qing *Tianxia* concept and internal perspective, Ryukyu was always viewed as a frontier dependency in the broad sense, similar to the Tusi (local chieftain) areas in the Southwest. This dual tribute was not a Qing ruling model but a two-pronged strategy adopted by frontier dependencies to ensure survival and interest. For instance, the Southwest Tusi paid tribute to both the Qing and neighboring states like Myanmar; border tribes adjacent to Russia and various Central Asian khanates often sought balance among different great powers before Xinjiang became a province. The current hype around the Ryukyu issue ignores this historical overlap of sovereignty and attempts to shoehorn it into the “Great Unification” narrative. This is a strategic political countermeasure conducted during escalating geopolitical conflict, using nationalist sentiment as a tool for international discourse. This also proves that current political forces are still accustomed to thinking about and handling external issues from an internal perspective, fundamentally showing a lack of respect for international norms and established rules of the game.

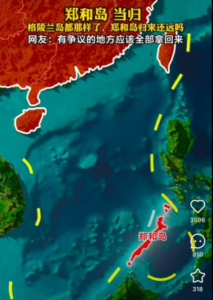

- “Zheng He Claim” on Palawan and the Refutation under International Law: Compared to Ryukyu’s complex dual history, the intensive claims of “Zheng He Island” (actually referring to Palawan, Philippines) that have suddenly appeared in recent months, while not officially endorsed, can be seen as a state-planned public opinion campaign or a form of pre-emptive positioning. The core goal of this operation is akin to the Anchoring Strategy in negotiation: first, presenting an extreme “high price” (the opponent’s hinterland) to force the baseline of geopolitical dispute negotiations to shift toward the extreme claim, hoping to gain greater leverage at the final point of compromise. Such claims satisfy the psychological need for national pride, but their essence is the extreme instrumentalization of historical rights, exceeding the framework of international law. Zheng He’s voyages only prove China’s historical maritime activity in the 15th century, not continuous sovereign exercise. According to international law, especially UNCLOS and its precedents, a territorial claim must demonstrate long-term, continuous, and effective administrative management and control. Just as Portugal’s ocean voyages do not grant it sovereign claims over the EU or the globe, China did not establish garrisons or continuous administration in these regions after Zheng He. This extreme rhetoric exploits the “Century of Humiliation” historical complex, aiming to stimulate populist emotion rather than seek rational, evidence-based geopolitical dialogue.

Conclusion: History Hijacked—From Psychological Gap to Political Myth Construction

The historical formation of the “sense of humiliation” may have its authenticity, stemming from the psychological gap between being the “center of the world” and merely a “regular player.” However, the continuous propagation of this rhetoric by modern political forces has evolved into a systemic populist emotional manipulation project targeting the populace. It deliberately magnifies the “victim” narrative to maintain its political legitimacy while obscuring China’s true position as a great power that successfully achieved territorial expansion and consolidation in modern history. This instrumentalization is not only a distortion of history but also a means of using national emotion to achieve political ends.

This historical perspective is informed in part by my own family’s experience. My ancestor, stemming from the Xiang Army lineage, served as the County Magistrate of Gaolan County—the historical administrative core from which Lanzhou later emerged, now the capital of Gansu Province—a critical logistical hub connecting the interior with Xinjiang during The Second-Class Marquis of Discipline and Tranquility, Zuo Zong-Tang’s reconquest.